Climate Anxiety and Mobilizing in Crisis

Curated by Chase Galis and Tatiana Carbonell

Common language surrounding climate change has invoked the vocabulary of urgency, using words like crisis and emergency to mobilize the public to fight its contributing factors. This rhetoric promotes the idea that contemporary climate crisis qualifies a “state of exception” in which diverse publics must be collectivized to combat a shared threat. Corporate and governmental bodies alike have coopted these strategies to shift the burden of environmental harm away from systems of extraction and pollution to an individual who is responsible for recycling more, consuming less, and otherwise managing the harmful consequences of their own behavior. Compounded with the ever-present threat of environmental catastrophe, individuals have been forced to reflect on their own position amid the material and political dimensions of an escalating planetary crisis.

These effects have even come to induce physiological conditions amongst which climate anxiety stands as one of the most prevalent. This term describes conditions of muscle tension, quickened breathing, and high heart rates attributed to fear of impending environmental disaster. Climate anxiety has been defined as “long-acting response broadly focused on a diffuse threat,” implying that its climate-induced expression is triggered by speculation of future scenarios in which ongoing environmental degradation has begun to produce disastrous consequences.

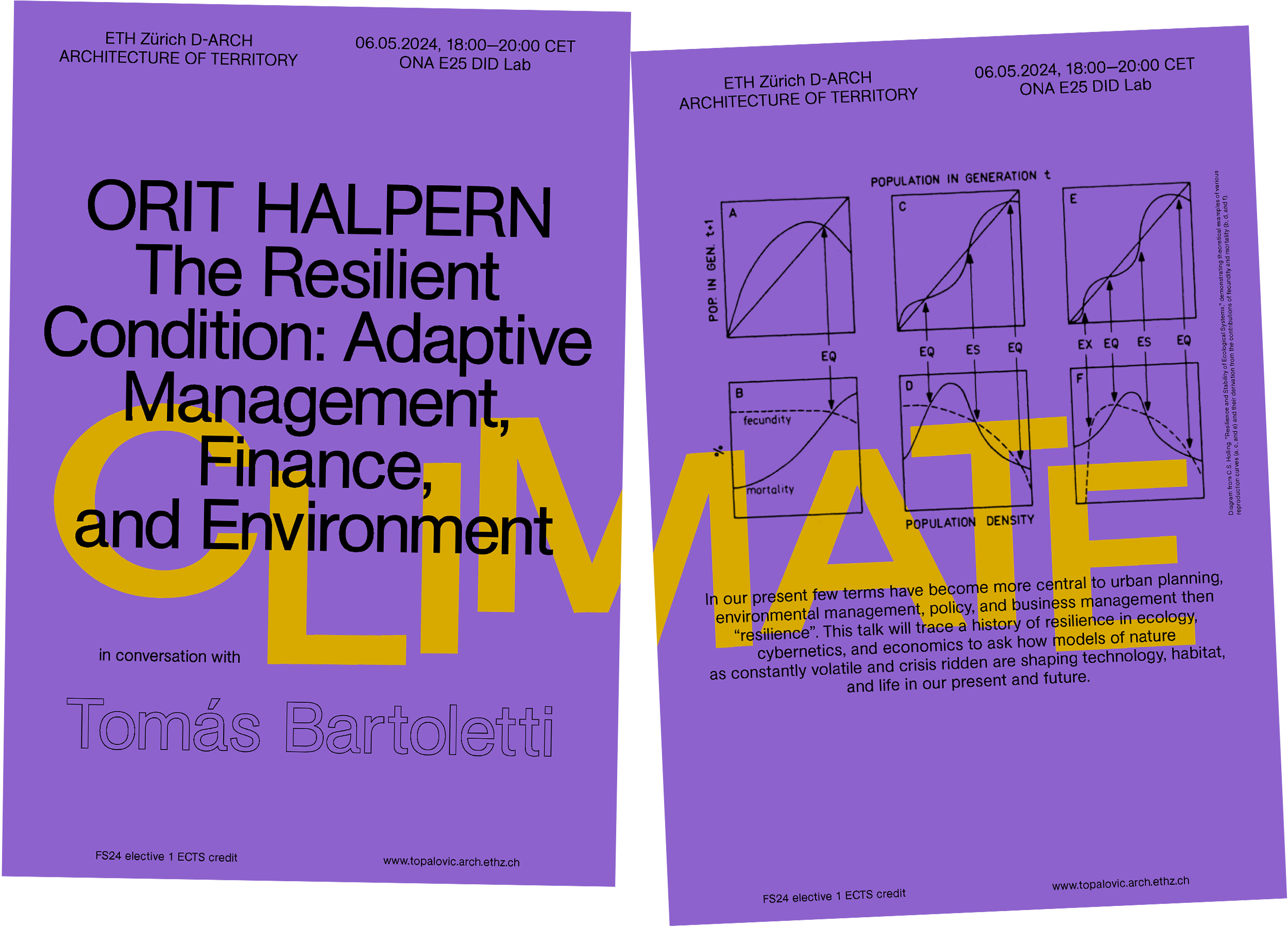

Differentiated from a singular weather event, literary and cultural historian Eva Horn suggests that climate resists representation in discrete images and description. She reminds that climate change is a longue durée that diffuses crisis over an extended temporal trajectory—what she coins a “catastrophe without event.” In response to Horn’s provocation, we look to the built environment as a register of the changing climate and its history. Processes of technological control have promised to draw the line protecting development from the undisciplined environment; however, climate crisis has threatened to break it—at the very least demonstrating how precarious this threshold is. Architecture has played a fundamental role in constructing this imaginary to appear safe and stable, providing form and materiality to the stasis of modern environmental relationships.

Architecture, in this sense, forms a bridge between two distant scales through which climate has been evaluated: that of the individual and that encompassing a greater sense of environment. Historian of science Deborah Coen asserts that the act of scaling in the study of climate “can also be a way of situating the known world in relation to times or places that are distant or otherwise inaccessible to direct experience. Scaling makes it possible to weigh the consequences of human actions at multiple removes and to coordinate action at multiple levels of governance.”

Taking the built environment as its field of inquiry, this lecture series looks beyond solution-finding under the climate crisis to better understand how individuals perceive their own subjective positions—their contributions, vulnerabilities, complicities, and anxieties—in the face of impending catastrophe. By shifting analysis between planetary scales and that of the body, we ask in what ways have built form and regulated land structured the way individuals locate themselves against the effects of climate change?